- Home

- Meshel Laurie

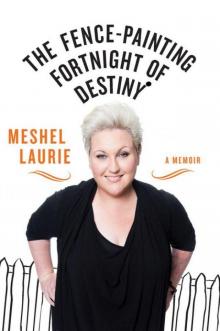

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir Page 12

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir Read online

Page 12

Merrick Watts was the hottest young comedian in town when I arrived in ’95. There was no Rosso yet—I’m not sure they’d even met at that stage—but Merrick was already forming the basis of the persona that would make him a household name, although his fashion sense has certainly evolved. Back then Merrick was known for having the snazziest old-man op-shop suits on the circuit. He even had those mahogany-coloured platform shoes to go with them. He looked great and his jokes were funny, but I’ll always remember him complimenting me on my gigs whenever he saw them. The back room could be a very lonely place for a newcomer. First-bracket or ‘try-out’ comics came and went pretty quickly, so very few people took the time to learn your name until you’d been around a while. Except Mez, who told me he enjoyed my stuff very early on, which really meant a lot because even though he was only my age (21 or 22 at the time), he was already headlining gigs.

Actually, there ended up being a big gang of us who were all around the same age. Rove was a member. He’d moved over from Perth not long before I’d arrived from Brisbane and was part of a double act called ‘Duff and Rove’. They did a lot of prop comedy and puppet shows and were fixtures at The Espy. Rove was obsessed with Warner Bros. cartoons, and I’m pretty sure he wore an official Warner Bros. T-shirt with a different character on it every single day. I seem to recall the ‘Marvin the Martian’ T-shirt got more runs than the others though. Rove met and fell in love with a beautiful actress from Sydney who helped him smarten up his act in fashion terms, but as I write Rove is working out of his own office at the Warner Bros. Studio Los Angeles. That dude must be running one hell of a vision-board because I’ve never known anyone to manifest their dreams like Rove.

He started pulling a few Foxtel gigs in the very early days of pay TV in Australia. At one stage he was a reporter on some kind of lifestyle show, with an equally anonymous Hugh Jackman. It was all a bit vague and he didn’t talk about it much, but it was clear to everyone when Rove started hosting a chat show on public access Channel 31 that he’d found his calling, and he loved it. I don’t think any of us ever really imagined that he would become a proper TV guy though. No stand-up comedian had ever done anything like that in our living memory, so it never occurred to us that we could do lots of things we ended up doing.

If Rove’s ascendance caught the rest of us off-guard, Hughesy’s defied reason! Back in 1995, Dave Hughes was the alpha male of a pack of comedy boys who all at one time lived in a share house together, and all hung out at The Espy. Dave became famous within the industry for telling the entire truth on stage about things most people wouldn’t tell their most trusted friends. I couldn’t possibly retell any of those stories here, but let’s just say that many of them involved his love life, which seemed to be clumsy but effective overall (if a tad expensive). He had one particular punchline, about an encounter with a lady that is still talked about today by those who witnessed it. He fearlessly used it in every gig, irrespective of how successful he’d been up to that point. At the time I thought it was dumb, but now I realise it was indicative of Dave’s attitude to stand-up and to life. He is fearless and unerringly honest about both, which is probably what has made him so successful, in radio in particular.

Dave was arguably most well known in the early days for doing routines about being on the dole, while he was still on the dole. Melbourne comedy ran on the dole in the early and mid-90s, as did every other sector of the arts. It allowed people to treat their art forms seriously and perfect them, and I for one make no apologies for it. Dave Hughes and his housemates self-produced a show for the Melbourne International Comedy Festival in 1996 called ‘Lying to the Government’, for which the ticket booking number was the landline into their house. The posters for the show were black-and-white photocopies and bore the logo of the DSS, (Department of Social Security, the forerunner to Centrelink). Famously, a lady rang the number on the poster one day, looking to buy tickets, and was told just to come to the gig and pay at the door. When she asked for directions to the venue, the dude who was taking her call enquired as to where she lived, then offered to pick her up on the way. So the cast did indeed give the audience member a lift to the gig. (I believe a representative from the DSS gave the number a bell too, but I seem to recall his enquiry taking a lot longer to resolve.)

Wil Anderson seemed to arrive fully formed. He was not the only young, handsome, funny guy on the circuit by any means—there were many there before him, but none worked as hard. They all wanted to be rock stars like Fleety and Marty, who appeared to put very little effort into their work, which was nonetheless brilliant. Wil took a different approach and worked really hard. He wrote and performed his first comedy festival show before he’d completed his first year of stand-up, which is pretty massive. Some people struggle to write an hour of new jokes a year; Wil did it in about three months and had a theme! Gutsy stuff.

Of course Wil evolved into a rock star later, with the painted nails and such, but has never lost the generous country boy attitude he brought to Melbourne from his parents’ dairy farm all those years ago. (Remember that, because it’ll become pertinent later on.)

Wil always knew how to charm the ladies, even if at first he didn’t really know what to do with them after that. The many young women who ran the Melbourne Comedy Festival always made sure Wil was looked after and had plenty of coverage in the paper. I seem to recall him taking them a basket of muffins in the lead-up to that first festival—a tip for young players. The downside of his effortless charm is that he had stalkers almost before he had fans. One of them slashed his tyres; another was introducing herself to his neighbours as his girlfriend when he wasn’t around. I’ve seen a few grown-up famous ladies behave strangely in his presence over the years too, but my feelings toward him have always been rather maternal. He’s not always as happy as I’d like him to be, but he’s still at his happiest when he’s doing good stand-up. Most people, myself included, find it a drag after a couple of decades, but he genuinely loves it and it shows.

Peter Helliar came along a bit later and was almost like a pet. He was so adorable and funny that everyone wanted to include him in everything they were doing. I scored a job writing jokes for In Melbourne Tonight in 1997 through my fairy godmother Julia Morris, who was a cast member. I did my first TV spots on that show and organised for Pete to do his. We took a video camera and made some little ‘behind the scenes’ bits and pieces to use in live gigs and it was all terribly exciting. However, something spectacular happened at Wimbledon that night and Pete’s spot was bumped at the last minute so the show could cross live to London. We were totally bummed out and went roaming the halls of the old Channel 9 site in Bendigo Street, Richmond. Eventually we stumbled upon the set for one of Ray Martin’s Top Blokes and Aussie Sheilas specials, so Pete stood up there in front of hundreds of empty chairs and did his whole routine. It was hilarious for all the reasons Pete is hilarious. It was sweet, self-conscious and daggy as hell.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw Alan Brough in the back room of The Espy, but then meeting Alan isn’t something anyone is likely to forget in a hurry. I remember thinking he was like a deliciously naughty schoolgirl trapped in the body of an enormous New Zealand man. His thick Kiwi accent was made all the more jaunty by his high-pitched exclamations and tendency to clamp his splayed fingers to his breast, suck in his cheeks and thrust his eyes skyward in a completely camp expression of mock horror. (We call it ‘clutching your pearls’.)

I introduced myself to him in the back room after his first performance to tell him I thought his spot had been excellent—sort of paying forward the good deed Merrick had done for me. I didn’t want him to be lonely because he was new. I needn’t have worried, because Alan was universally adored within days of his arrival and his performance was great because he’d been working successfully in New Zealand for years. He was terribly gracious at the time, thanking me and mentioning off-hand that he’d done a bit of comedy before. He was another one that everyone in comedy wanted

to work with, but over the years we’ve had to share him with the film industry and big-budget musical theatre. Alan is living proof that a person who is as delightful as they are hugely talented will never be out of work, no matter how humorous their accent and effeminate their exclamations.

Speaking of which, Adam Richard was always fabulous. He and I ended up sharing most of the MC duties in Melbourne for a couple of years, the only downside of which was that we rarely got to work together. I was, however, present one memorable evening when he was compering a heat of the Triple J ‘Raw Comedy’ competition for new comics. One act was so bad that Adam simply walked on stage afterwards, revealed a can of Glen 20 from behind his back and sprayed the entire stage without saying a single word. We in the crowd laughed that guilty laugh of relief that he’d taken back control of our ship, and he threw to a fifteen-minute break, like the skilful comedian he is. As MCs we both operated on the ‘less is more’ principle and always brought the gig in on time.

(Fun fact: Adam Richard, Tim ‘Rosso’ Ross and Corinne Grant all attended Swinburne University together before taking their chances in Melbourne comedy.)

I did my first comedy festival show in 1997. It was a two-hander I wrote and performed with Corinne Grant called ‘Dairy Belles’, about two country girls who’d moved to the city to become famous. We wrote songs and everything! I also got to perform in the main room of the Melbourne Town Hall, which seats about 3000 people, as part of the annual all-girl show, ‘Upfront’. That kind of crowd is a stirring sight to gaze out upon from a solitary stage. Judith Lucy, Denise Scott, Lynda Gibson and Rachel Berger were all on the bill that night. In typical style Rachel Berger walked over and introduced herself to me. To me! I was floored. How did she even know who I was? Why would she make the effort? As I got to know Rachel over the years I learnt how typical this gracious, generous act had been of her character. She’s a real lady, that one. She taught me a lot about feminism in action. I often stop myself in certain situations and remember conversations I’ve had with her to help me move forward in the right and dignified way.

In the next photo I am backstage at ‘Upfront’ helping the stunning Kim Hope with her corset while the disturbed Linda Haggar and Fahey Younger look on. They were a bizarre double act called Miss Itchy, who won the first-ever ‘best of the fest’ award in Melbourne, which is now called The Barry. Linda, on the left, is my best friend today. I took batteries and fried rice up to her and her husband Wayne a few days after they’d stood on their roof and fought the Black Saturday fires while their grandchildren huddled inside. She concentrates on visual art now, and one of her paintings was used as cover art on the final report of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission. Her main gig is art therapy, through which she helps the local kids express their feelings about the fires through art. Pretty high-falutin’ when you consider that the first time I met her she was wearing overalls covered in meat, and was chasing live crickets around a stage. She’s a mad old nanna but I love her so.

Even back then, when the Melbourne International Comedy Festival was a fraction of the size it is now, it was a very important trade fair that could catapult a career. It was a chance to showcase yourself to industry and media through gigs like ‘Upfront’, but also through hour-long shows in and around the Town Hall, like our ‘Dairy Belles’. There were even audiences for little shows like ours back then, because there weren’t as many superstars performing and because Melbourne has always had an audience for every kind of comedy. There were a lot of tickets given away for free too, but I was really proud of ‘Dairy Belles’ and loved performing it for anyone who wanted to see it.

Linda Haggar and Fahey Younger in the background—together they are ‘Miss Itchy’. Me assisting Kim Hope in the foreground, backstage in the Melbourne Town Hall during Comedy Festival 1998. (Photograph—Peter Milne, courtesy of M.33, Melbourne.)

Corinne and I were professionally produced by Token Productions, which was a very big deal. Token was actually two guys, Kevin Whyte and Angus Bell, who sat in a room in Fitzroy, using old doors as desks, establishing Australia’s first artist management agency catering specifically to comedians. These two were in their early twenties, but were already managing the careers of the superstars of the day in Greg Fleet, Anthony Morgan, Sue-Ann Post and Judith Lucy, who were not only substantially older, but also had personalities I’ll describe politely as ‘larger than life’.

Token was a gutsy crew and everyone wanted to be associated with them. Since arriving in Melbourne, I’d had somewhat of a dream run. I’d put together some good jokes during my fourteen months in Brisbane, so while everyone thought of me as brand-new, I actually had some experience behind me and stood out from the newbie pack. I was starting to pull some great gigs and Token was throwing a lot of work my way—including a two-week support spot with Judith Lucy, which was amazing.

I was thrilled when Token offered to produce a show for me, and let me choose my co-star. I’d seen Corinne perform a few times, and thought her guitar would come in handy, so Angus came to The Espy one Sunday to check her out, and it was on.

Not for the last time, I did myself a mischief by assuming I knew what would happen next. I thought that by festival’s end, I’d be the newest and youngest member of the Token family, that my name would join that illustrious list of talent, and my photo would be Blu-Tacked to the Fitzroy wall alongside theirs. None of that happened. By festival’s end Wil Anderson and Corinne Grant’s photos were on the wall, and I was back on the outside looking in for the next few years.

I must have been an arsehole during that season of ‘Dairy Belles’. I don’t remember being one, and I just couldn’t bear to ask anyone directly, but I must’ve been to have been passed over like that. It was an incredibly painful lesson in what happens when I count my chickens before they’ve hatched. I wish I could say I learnt my lesson, but I’ve had to learn it so many painful times since then that it’s just embarrassing.

Over the next two years Rove, Hughesy, Merrick and Rosso, and Peter Helliar joined Wil and Corinne on the Token wall, and on the line-ups of the best gigs in Australia. They started pushing into television as hosts, where comedians had previously existed only as writers and guests, and radio was paying attention too. They were also making some real money. I was so broke I used to walk home from The Espy with my eyes glued to the ground, hoping to spot some change with which to buy dinner. I was not Zen, I can assure you. I was pissed off.

The first couple of years in Melbourne had run exactly according to plan, but suddenly I felt like I was watching other people living my life. I wasn’t getting those great gigs anymore because the Token kids were getting them. I’d sort of been demoted as a result of my first comedy festival, which was not the way it was supposed to go at all.

I was in a tailspin actually.

Oh, and I was also a newlywed.

I GOT MARRIED

I’ll have to backtrack slightly here, to tell you about the other stuff that was going on in 1996 when I wasn’t cruising around the place, laughing and drinking with my mates like I was in some kind of endless schoolies week. I was also setting up house with the love of my life and I have Paul Keating to thank.

In 1996 the Keating government started making movements towards what the Howard Government would eventually christen ‘work for the dole’. It was a lot less intrusive than it became, although it still seemed at the time like a very rude affront to the arts.

To continue to receive unemployment benefits, I was told I’d have to sign up for one of these programs where I’d learn how to get a job. They kept trying to send me to graphic design courses—that’s where they tried to send everyone with any kind of creative bent. I kept saying no because even though I didn’t know what graphic design actually worked out to be on a day-to-day basis, I knew it required some amount of talent which I rightly assumed I didn’t have. Eventually, my case manager was delighted to inform me that she had found a course that was perfect, although I wasn’t strictly elig

ible because it was across town. We decided to apply anyway, mainly on my part to keep her busy and off my back for a few weeks. I assumed I wouldn’t be accepted because it was specifically for performers, and of course there were plenty of those stinking up the dole queues in every part of town, so why would they find room for me? Lo and behold they did, and the next thing I knew I was on the number 19 tram to Brunswick where the Salvos had taken over an old bank and were fixing to teach a bunch of actors how to create their own work (and get off the dole).

Upon my arrival I was informed that the performers would be congregating upstairs. The large downstairs space was reserved for the visual artists, painters and sculptors, who’d mainly be learning how to run a gallery (and get off the dole).

I was very relieved by the lunchbreak on that first day. By then we’d discovered we’d be getting about 50 per cent more than the dole for the duration of the twelve-week program, and that we were excused from attending whenever we had auditions or other opportunities to find work (and get off the dole). One of the actors piped up defensively, enquiring as to whether casting directors and agents were expected to supply some kind of note as proof of our whereabouts when not at the program. We were assured that would not be necessary, which meant it would be really easy to wriggle out of attending the program. The Salvos received a certain amount of money from the government for every person in their program, so the last thing in the world they wanted was to kick anyone off. It was a live-and-let-live scenario, but because it was a building full of young artistic types it was actually quite fun, and we ended up attending most of the time. For a while anyway.

On that first day in the old bank on Sydney Road, I decided to go for a lunchtime wander as I’d never been up that way before. I was checking out the artwork that was being hung downstairs, and one piece in particular caught my eye. It was an enormous canvas featuring an abstract oil painting that reminded me of Salvador Dali’s work. It was all distorted humanoid forms, melting together, but stretching tightly apart against the backdrop of breathtaking sunset. As I stood there it occurred to me that I was about to come into some money, in the form of that 50 per cent pay rise from Uncle Paul. ‘I might buy myself a bloody painting!’ I thought. I’d never even known anyone who’d had an original oil painting hanging in their house, and as my sole aim at that time was to be different to everyone I’d ever known I thought it was a sterling idea.

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir