- Home

- Meshel Laurie

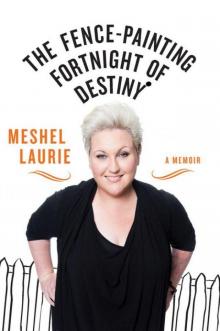

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir Page 8

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir Read online

Page 8

My grandad was my best friend. Thirty years since his death, it makes me cry to write those simple things about him, but it also inspires me to make that effort with my own kids, to try to make them feel like there’s nowhere else I’d rather be than wherever they are—which, frankly, will sometimes be a lie, but as long as they believe it I’m okay with that.

Anyway, later that day, the day he died, I was sitting at his kitchen table where I’d spent so many simple, brilliant hours with him. His minister talked about flowers and hymns, Grandma made endless cups of tea, as grieving women did back then, and my dad doodled on a piece of paper and was terribly quiet, which I found disconcerting. Up until that day, I would never have described my dad as ‘quiet’. Now I realise that he was only 32, had no siblings with whom to share the load, and was probably a bit overwhelmed with his new status as head man of our little tribe.

He assumed the responsibility of caring for his mum. We spent even more time with her than we had before, which was a lot, and he was first on the scene when her house was broken into one night while she was out playing cards. She came home to find the place ransacked and Grandad’s dog limping after being belted with a lump of wood by the intruders. Dad went straight to the local hardware shop (which was owned by an actual bloke, because none of us had ever heard of Bunnings) and set about beefing up her security, but I can’t imagine how vulnerable she felt, living alone for the first time in her life.

As far as I know, no one suggested she should move in with us. In fact, Grandma’s own mother, Grandma Heath, had been living alone just around the corner since her own husband had died about twenty years previously, and our beloved Aunty Greta was living alone one street over since the death of Uncle Siddie about a year before Grandad. None of them showed the slightest bit of interest in moving in together for security or company. Grandma Heath simply shut down most of her house by throwing white sheets over everything and closing the doors, leaving herself with the kitchen, bathroom and an enclosed verandah in which to live her life. Aunty Greta spent most of her days tending to her wood stove, which needed constant supervision or she’d be left without hot water (yes, even into the 1990s her hot water came from the wood stove).

They were an independent bunch, but the break-in shook them all up, and we’ll never know how big a part it played in Grandma’s burgeoning friendship with a tall, graceful widower at her church named Vince.

The two of them came over to our house one night, about a year after Grandad died, and I was not impressed. ‘Too soon!’ I’d have said if I’d had the vocab. ‘What the hell are you thinking girl?’ I’d have exclaimed if I was the African American diva I’ve always dreamed of being. Instead I just sat quietly in my dressing gown, performing the odd party trick when required, and wishing they’d hurry up and leave so I could tell Mum not to let it happen again.

As soon as the door closed behind them, and in a scene eerily reminiscent of the day my grandad died, Mum and Dad sat down and comforted me as they started talking about Vince being part of our family. ‘Oh for fuck’s sake!’ I’d have said, if I knew then what I know now.

Don’t get me wrong, Vince wasn’t a bad guy, but the amalgamation of our two families just didn’t take. No matter how hard he and his kids, and my mum and dad and our family tried, we just never felt comfortable in their presence, and I’m sure they never relaxed in ours. I’m sure a lot of it had to do with the fact that they were ‘from the land’.

Vince had been successful enough to be able to gift his farm to one of his kids, at which point he and his wife had retired in town. One of his sons-in-law did the stock report on the local news, which we thought was very flash indeed. They definitely had an air of bush aristocracy about them. I think my parents always felt a bit inferior to Vince’s family for that reason, and we kids picked up on it and felt pretty low about ourselves in their company too.

So all in all it was awkward as hell, and didn’t improve when Vince and Grandma got married. Grandma’s life began to change in lots of ways, including some that really hurt my little heart. She gave us Grandad’s dog for one thing. He was a beautiful German shepherd who’d never needed a fence, he was so well behaved, and who scuttled straight under the steps when Grandad told him to. I was glad to have him, but I couldn’t believe she could bear to be parted from him. I could never give my dog away, especially if I’d shared him with Grandad. Sometimes she just didn’t feel like the same person anymore.

Little did I know what my father was trying to work through. By that time Australia was in recession and my father had mortgages on our house and on his business, a taxi, and found himself paying between 14 and 17 per cent interest on those loans. (Mortgage interest rates in 2012 hovered around 5.5 per cent.)

He had three kids to feed and educate, and he and his wife worked every hour God sent to keep paying the bills, the mortgages and the tax man. Eventually, in desperation, he asked his mother for help. She agreed to loan him some money, but charged him interest. In fairness, she did charge a lower rate than the bank, but she made it clear that it was a pain to withdraw money from her accounts because, as she put it, the bank’s high interest rates were very good for people like her because they really bolstered her savings. Yet those very same interest rates were killing her only child. Is it possible she didn’t realise? Could she really have been that insensitive?

She once asked my father to hide tens of thousands of dollars for her so she could keep getting the pension. Was she really that cruel?

Grandma Heath was suddenly deemed unable to care for herself by Grandma and her sisters. She was placed in a nursing home, which she despised, her house sold, and proceeds divvied up between the sisters. Was Grandma actually greedy?

Grandma Heath died after a couple of years in that place, and Aunty Greta and her sisters died soon after that. In the space of ten years, my father had lost every person who’d nurtured him through childhood. Although his mother was still alive, they’d finally become estranged in the mid-’80s.

The one constant in my father’s life was work. As a taxi driver, his hours were up to him, and he used every one of them. He worked seven days a week, without question. Early in the week he’d leave the house by about 7.30 a.m. and be back by about 8 p.m., having spent about an hour at the pub, and ready to drink a bit more before falling into bed. The weekends, though, were hard-core. He’d leave at 7.30 a.m. Friday morning as usual. He’d work all day and all night, until the drunks started to drop off at about 5 a.m. Saturday morning. He’d be back in the taxi by 9 a.m. Saturday morning and do it all again, climbing into his own bed around 6 a.m. Sunday morning. By 9 a.m. he was back in the saddle, although Sunday evening he took an early mark and made his way to the pub at around 4 p.m. I spent most of the weekend drinking, so Sunday night was usually the first time I’d see him in days, and in the nervous lead-up on Sunday afternoon, I’d often find myself humming one of my favourite songs: ‘Bad, Bad Leroy Brown’.

By the time he came home at about 7 p.m. on a Sunday night he was drunk, exhausted, pissed off and meaner than a junkyard dog, as my favourite song would say. Unfortunately, unlike Leroy Brown, he was not on the south side of Chicago, but raging in the kitchen, generally in my direction. Sometimes I’d fight back; sometimes I’d stand still, trying to think of other things until it was over. It just depended on how angry I was at the injustice of it all. ‘Just don’t answer back’ was Mum’s advice, and I could see that it made sense. The whole thing blew over quicker if I didn’t put up a fight, but where was the dignity? Where was the truth in all this screaming and ranting and raving? I didn’t know what his problem was—I didn’t understand the economic or maternal pressures he was under—but I knew it had nothing to do with me. How could he possibly hate me as thoroughly and suddenly as he appeared to? I hardly ever saw the guy!

As the rest of the family sat in another room, keeping their heads down and pretending to watch 60 Minutes, I’d stand alone, waiting for it to end and for him to wander off

to bed. The poor, broken man.

Of course it really didn’t matter what I did or didn’t do on those Sunday nights; it had nothing to do with me. I was a lightning rod for his anger, disappointment and hurt. I can only assume I represented something that deepened the pain and the fear of what his life was turning into. Things had become very complicated in the short period of time in which I’d transformed from his little girl into an independent teenager. A great many other things were slipping from his grasp just as quickly as I was.

I stopped calling my father ‘Dad’ around that time. I can’t remember ever deciding not to—I think it just didn’t feel right anymore, because dads are people who love you, and he really hated me. I didn’t call him anything for a while, which wasn’t difficult because I barely laid eyes on him for about ten years. Somewhere in the middle, though, I gave him a beautiful puppy called Troy, and I jokingly told my father he was Troy’s ‘Pop’. I’ve called both my parents Nan and Pop ever since. I suppose it helps me distance myself from the pain of those years and push forward with a relationship now.

We never discuss those days, and judging by my own reaction to writing about them, I think it’s probably for the best. I know there’s an assumption that ‘getting things out in the open’ and ‘just being honest’ are intrinsically positive things, and important parts of the healing process, but I don’t think they necessarily are. I think there is something to be said for letting sleeping dogs lie—for quiet, personal forgiveness without fanfare. That’s what I’ve managed to do. I’ve forgiven my father, even though he’s never asked for my forgiveness. For all I know, he might be completely unaware he needed to be forgiven: he was pretty pissed at the time! I had to do it for myself though, to create peace and gentleness in my own mind, otherwise those Sunday nights in the ’80s could have kept on hurting me forever.

Obviously the experience toughened me up. When you’ve stood firm in the face of your own father’s hate with nothing but your dignity as a weapon, it’s hard to see anything or anyone as truly intimidating ever again. I know I have to be grateful for that, because it’s played a big part in my reaching the happy life I live now. Quite simply, I never give up.

Nowadays, we hear so much about the importance of the first seven years in a child’s life. Experts say that strong self-esteem and self-worth in a seven-year-old will last for life. Perhaps that’s my secret—my first seven years were pretty idyllic, after all. Maybe that gave me the fortitude to withstand the shit-storm that followed, and prevented me believing I was nothing and no one.

Consciously or unconsciously, I’ve ended up pursuing some pretty volatile professions, from stand-up comedy to the sex industry to commercial radio. There have been times in each when I thought it really might break me, and my husband has begged me to consider a ‘tactical retreat’, but back in the day, when my father was my enemy, there was simply nowhere to retreat to. I had no option but to stand my ground, raise my shields and wait until he wore himself out. It’s a process I’ve repeated a million times over in my life, and I have to say I think it’s been pretty helpful overall.

I don’t feel arrogant about any of that. I wish I was one of those cute, quiet women whose fathers adored them and gave them flowers on Valentine’s Day. I can spot those chicks a mile away. There’s something about the effortlessness of their social interactions and their trusting natures that screams, ‘I can go back to Dad’s if ever this gets too rough, and he’ll wrap his arms around me and promise it’ll be alright.’ Oh how I envy those women.

As for my father, he is now a gentle old man, in whom we see flashes of the cheeky youngster. He and Mum have recently left Toowoomba to live closer to me, and I’m occasionally called upon to act as the head of our little tribe. He is a tentative grandfather to my children. Having had so much confidence knocked out of him over the years, he lacks the ease his own father brought to the role, but my babies ask to visit him constantly, which suggests to me that they feel he enjoys their company, and misses them when they’re not around.

I can’t ask for more than that.

SEX, DRUGS AND

ROCK’N’ROLL—BUT MOSTLY

DRUGS AND UNI

The first thing I did upon leaving high school was to sign up for the dole. My parents thought it was a disgrace, and told me so every single day. A number of my frenemies told me so too, as they embarked on degrees they’d never complete, and apprenticeships they had no interest in, because they were parroting the views of their conservative parents, as country kids tend to do.

All of that told me I was on the right track.

My biggest fear was waking up in Toowoomba at 35, having forgotten to get out. I suspected that many seventeen-year-olds before me had made big plans, but found themselves waylaid by a job they meant to be temporary, and a relationship they thought was a fling. I was convinced at seventeen that I stood atop a slippery slope that could lead me straight to a life of working for some local hero wanker, fighting another one for child support, and putting all my energies into Saturday nights at Rumours chasing others just like them. I was genuinely scared I’d wake up one morning and forget about my dreams—or worse still, laugh about them.

Role-playing suburban parties was a bit of fun while we were at school, but within months of leaving school I was watching girls my age embracing the lifestyle. That, I thought, was pathetic, and refusing to get a job was my first blow for freedom. It was a signal to anyone who was interested that I was not following the program, and it was so scandalous it made me giddy with delight.

I wanted to go to uni to study acting because I was lonely, really. I pinned my hopes on it attracting other people like me, and hoped I might find some company for my long journey ahead. My academic record excluded me from attending right after Year 12, so I took a few TAFE courses at night in that gap year to bolster my chances.

One of which was ‘Computers’.

When I was in Year 12 in 1990, our school had a computer room. It housed about a dozen computers, which meant that two or three girls would huddle around each one, taking turns making it do stuff. Those computers were very limited in terms of stuff they could do.

The school ensured each class had one session a week in the computer room. In my case, it was part of Economics with Mr Shirley, who was characteristically philosophical about our sessions. We used a program that simulated the Australian economy, and was even more boring than it sounds because there were no graphics or noises, as these hadn’t been invented yet. There was a bright blue screen with a list of things that governments spend on, and a throbbing square cursor prompting us to increase or decrease spending on each by arrowing up and down and using the < or > buttons. After we’d made our way through the list, it would tell us what our gross domestic product and unemployment rates were. Quite anticlimactic and abstract, not unlike deciphering an actual federal budget, so bravo for realism I suppose.

So instead we spent a lot of our sessions at the park with Mr Shirley, enjoying God’s creation. With no mouse, no Windows, no internet, just the bright blue screen, throbbing cursor and MS Dos log-in codes we could never remember, there wasn’t a lot to enjoy in the computer room.

‘Computers’ at TAFE was better for two reasons. Firstly, Windows had been invented, so there was actually stuff to do that was really interesting. The class was literally about learning to use word processing and spreadsheets, which were kind of mind-blowing at the time. Perhaps little Sister Chesty was right about typing and shorthand, because there was something really empowering about learning a skill. I left every Tuesday night feeling more capable.

Secondly, I was allowed to go home when I had finished the night’s work—such a sensible, civilised approach, don’t you think? If only everyone was allowed to go home when their work was done, instead of scheduling meetings with each other to look busy until the appointed hour, at which time they all log off as one, then fight their way out of the car park or onto the train. Imagine if we humans were given the responsib

ility of deciding for ourselves when our daily work was done. We wouldn’t have to do everything at the same time as everyone else. Think of the easing of traffic congestion, think of the free treadmills at the gym, think of the efficiency if everyone knew that as soon as they did everything they had to do at work, they could leave!

Yes, in a lot of ways, ‘Computers’ was utopia. Everyone else in the class was really old and completely baffled—many had never used a keyboard before. I often think back to that class when I’m watching my toddlers wield my iPad. Man, I’ve seen a lot of crazy stuff since the ’70s. What a wonderful time to be alive in a lucky country like Australia.

Anyway, ‘Computers’ did the trick because I was accepted into uni the following year. I applied and auditioned for all the good ones in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane, but of course was only offered a place at the University of Southern Queensland in Toowoomba. I say ‘of course’ because I was beginning to notice a pattern developing in my life, in that nothing ever seemed to come easily to me. No bolts of lightning, no lucky breaks, or amazing coincidental twists of serendipity. Just a lot of putting up my shields and waiting.

I felt I had no real choice but to accept the offer and be happy that I was at least moving in the right direction, albeit very slowly. I was eighteen by then, and I’d planned to be a stunning Melbourne ‘it’ girl and dating Paul McDermott by 25. I was frustrated but determined when I entered my first year of university, which I thought would be a fairly insignificant little sidestep on my way to a Dogs in Space life in Melbourne. I was hoping to find a travelling companion and I did, in a way.

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir

The Fence-Painting Fortnight of Destiny: A memoir